Programming in the classroom is hot. It’s become the software equivalent of iPads–everyone has to try it and missing Hour of Code risks losing your Tech Teacher stripes.

Programming in the classroom is hot. It’s become the software equivalent of iPads–everyone has to try it and missing Hour of Code risks losing your Tech Teacher stripes.

Who would think the geeky cousin of math and science would become so popular? Thanks in equal parts to Khan Academy and Common Core, the fundamental core of programming–students as problem solvers–has moved from theory to practice. Common Core provides strategies in its Standards for Mathematical Practice and Khan Academy provides the mechanism in its highly-popular (free) computer programming courses.

This follows such worthy programming adventures like Scratch and Alice, originally geared for Middle School, but their immense popularity and intuitive approach inspired games like Tynker, Blockly and the wildly popular Robot Turtles for youngers, each more fun and simpler than the last. We’re not talking C++ or Fortran or DOS. These offerings are intuitive, forgiving, and emphasize observing, testing, thinking, trying, failing, and trying again.

Traditional programming, with formulas and symbols and frightening words like ‘algorithm’ and ‘script’, is mostly relegated to fifth grade and up.

Enter Primo.

“We are working on a tool that empowers children to become creators, and not just consumers within the digitalised world we live in. Programming is an incredible tool that empowers people, it changes the perspective on problem solving and logic in general. … Mastering logic from an early stage of learning creates the right mind set to assimilate more notion-related content. … Skills are mastered gradually. … Think of Primo as the very first step in a child’s programming education. Primo provides the very basic ABC of programming logic.”

More suited to the sensibilities of pre-k than computer-based cousins, Primo (by London-based Solid Labs) is an intuitive, tactile, non-computer or iPad game, designed to introduce programming logic to children ages 4-7. Without requiring reading, writing, math, or prior programming knowledge, it takes players from a basic introduction all the way to the command line. Let me repeat that phrase in case you missed it:

Primo does not require a computer, a laptop, or iPad. Not even a smartphone.

From the start, it looks playful, non-threatening, like a game. Its brightly colored wood blocks are an interface children are used to, and understand.

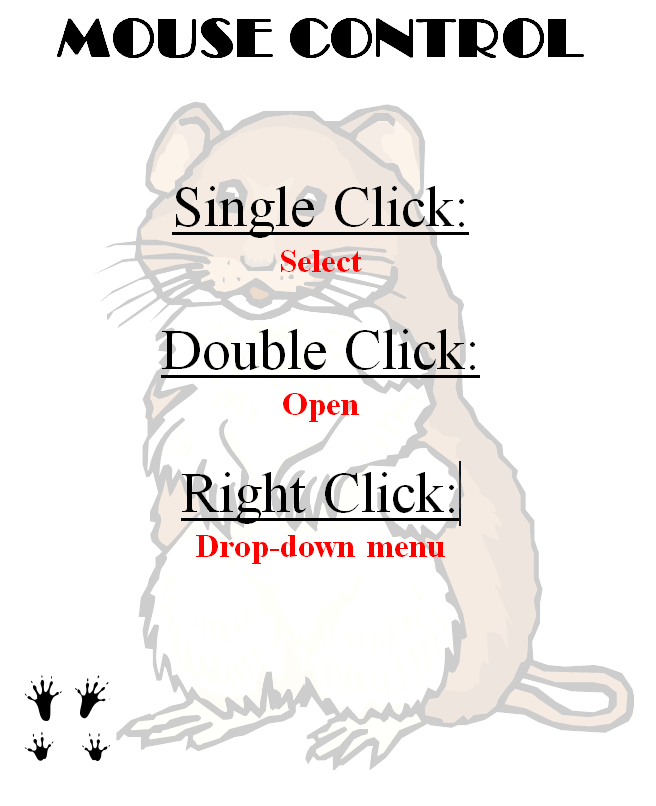

To play, children select pieces, insert them into holes in a box–called an ‘interface’–and push a bright red round button that sits all by itself to the right side. Any three-year-old will see that spot as where you go to make things work. ‘Start’ causes a robot (called Cubetto) to move. In fact, Cubetto follows the child’s orders–whether intentional or arbitrary–by moving according to the order of the blocks the child lined up on the interface. If these were placed haphazardly, the child soon learns that moving the pegs around changes how Cubetto moves.

Order counts.

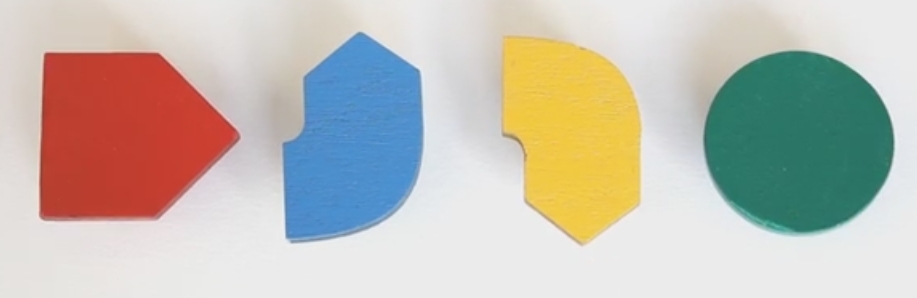

Children make a cognitive leap: They can help Cubetto get home (or wherever the child wants the cute square wooden robot to go) by arranging pegs with a purpose. The child can pick both the destination and the method of getting there (you might say they recognize a problem that must be solved), then select colored shapes that will get Cubetto around a corner, into a parking space, or to visit a friend. Each different shape represents a different action–from left to right below: forward, left, right, function (drops the flow of action to the green-encircled line at the bottom of the interface every time it is encountered).

Whatever order children choose, when Start is pushed, Cubetto follows the predesigned path from here to there. Children easily figure out a destination can be chosen (say, a tree for a picnic), and Cubetto can be ‘programmed’ by choosing specific blocks, inserting them in a unique spot on the interface, and pushing ‘Start’ (aka ‘compile’). If it doesn’t work, say, Cubetto passes by his destination, the child figures out what went wrong, fixes it (aka ‘debug’), and tries again.

All this time, the child thinks s/he is playing a game when what they’re really doing is learning problem-solving, critical thinking, about a programming ‘queue’, the importance of order, the appeal of cause and effect, how to follow multi-step directions, and how to be critical thinkers. Who would think four year olds were ready for that many higher order thinking skills?

The creators of Primo thought so, and they are right.

“The coolest thing we have seen a child do is master the infinite loop on the physical interface.”

–Yacob, creator.

Primo is low tech, all the programming wires and doodads hidden beneath the wood. The program is open source so anyone can hack the electronics and improve on it, customize it, or just fiddle around. The creators have all of the documentation online for free in what is called a ‘Maker Manual’.

Let’s sum up: an expensive wooden block game that requires 4-year-olds to think, whose creators decided to give all their schematics away for free for the asking. Did I miss something? Who would fund that start-up?

Kickstarter did in 2013, at 162% its asking funds. 162%! That’s amazing, for a game that teaches children to program–a historically under-attended class in middle school and high school. What is the big push to put children into programming before kindergarten? The answer is–there is no push. It’s a pull. Kids love the presentation of Primo, the hands-on feel, the interactive physicality. And the fact that they can affect their world, even at the tender age of three.

But don’t pull your wallet out yet. Their first batch is sold out. You’ll have to wait.

Education Applications

Because it’s sturdy, appealing and intuitive, Primo would fit in any preschool and kindergarten classroom. No instruction is required because it is as familiar as building blocks and peg boards. Students will pop colored blocks in holes–likely randomly–then eventually get around to the one block that won’t come out of the hole–the red ‘Start’. They’ll slap at it and Cubetto moves. It won’t take long to recognize the cause and effect between the arrangement of the blocks and the robot moving.

Watching the realization dawn on the child will be more fun than any adult has the right to experience. Children will learn Primo faster by themselves because of the way their tiny brains work. It truly makes teachers ‘guide on the side’ not ‘sage on the stage’.

When students have taught themselves the skills, have challenges ready for them. Who can get Cubetto to this tree? Out the door? Back in the box where it is stored? Kids will figure it out and learn a lot along the way.

This will be a solid addition to Hour of Code in the Spring, for those youngers who were likely left out of the fun.

–republished from my article on TeachHUB

More Hour of Code ideas:

Microsoft Hour of Code for Students

Jacqui Murray has been teaching K-18 technology for 30 years. She is the editor/author of over a hundred tech ed resources including a K-12 technology curriculum, K-8 keyboard curriculum, K-8 Digital Citizenship curriculum. She is an adjunct professor in tech ed, Master Teacher, webmaster for four blogs, an Amazon Vine Voice, CSTA presentation reviewer, freelance journalist on tech ed topics, contributor to NEA Today, and author of the tech thrillers, To Hunt a Sub and Twenty-four Days. You can find her resources at Structured Learning.

I love this! Thank you for the great ideas! I’m thinking of writing a grant for this.

Yep, this is a good one. Let me know how your grant goes.