With classwork and homework now heavily digital, the days of “the dog ate my homework” are gone. It’s simple to track, isn’t it? It’s right on the student’s LMS account or in their digital portfolio, somewhere in the cloud.

With classwork and homework now heavily digital, the days of “the dog ate my homework” are gone. It’s simple to track, isn’t it? It’s right on the student’s LMS account or in their digital portfolio, somewhere in the cloud.

Maybe. But the latest excuses are even more frightening — “Someone stole it from my digital file” or “The cloud ate it”. Every adult I know (myself included) has lost a critical, time-sucking digital file. It was saved wrong or got corrupted or simply vanished. The reason doesn’t matter. All that matters is that a week’s worth of work is now forever-gone.

Saving work correctly on a digital device isn’t as easy as it sounds. There’s a learning curve to knowing where to save, how to do that correctly, and then ultimately how to retrieve it. It can be especially complicated for students who use a different digital device at home than the one they use at school. Sure, it’s pretty easy if saved to a school-centric cloud account (like Google or One Drive) but that’s not always the case. If students use an online webtool, their work could be saved in that webtool’s server or as a link rather than a file.

Most kids learn how to properly save/retrieve digital files by suffering a painful experience. Before that happens, teach them this first place to look when save fails and they must search for it:

- Go to the digital device’s general Search field. This will find the file if it’s on that digital device or any drive connected to it.

- Search for the exact name or whatever part of the name is known. If you’ve taught students to always include their last name in a filename, they will now thank you!

- If they don’t know the file name but do know the file extension (maybe it was created in Google Docs or Excel), search for that using the general search term: *.[extension]. In this case, * is a general search term and replaces the file name. If they don’t even have that much information, look down this page under “When did you create the file?” for help.

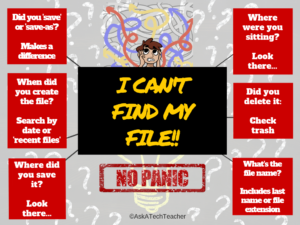

I start students saving their own files and understanding what that means as soon as they create work on a digital device they want to be able to find at a later date. I start very (very) simply and scaffold year to year. When they can’t find a project, here are six questions they can ask themselves:

A note before starting: Don’t answer these for students. Let them experience the thrill of critically thinking through how to solve this problem successfully.

Where did you save it?

Most programs have a default location where files are saved. This may be preset by the school (or parents) or it may be the system default. Where is that? If the student doesn’t know, this is a good time to have them ask that question.

Next, show them how to granularly discover where a file is saved. This is simple to do: The first time they save a project, the program tells them where that is. Show students how that works.

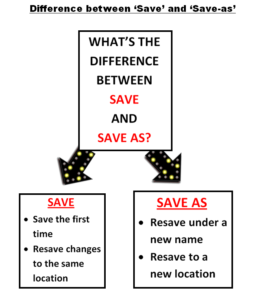

Did you “save” or “save-as”?

“Save” puts the file in the same spot it was opened. It takes about half a second so students love this time-saving approach. “Save-as” is employed only to change the location where it’s saved or the name under which it’s saved. I teach students to stick with “Save”. Some students want to be sure it’s saved so use “Save-as” and invariably lose it under the wrong name or wrong location.

Having said that, let students think about how they saved the file.

What’s the file name?

Elementary-age students rarely know the file name. Starting in kindergarten, I ask them to save with their last name in the filename but don’t enforce it until about second grade. I do ask them about the filename to get them to think about it. If they don’t know the filename, how do they expect to find it?

That logic usually makes sense to them.

When did you create the file?

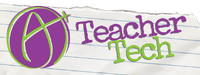

Surprisingly often, students can pin down the date they created a file with help from classmates. They know when they were in the computer lab working on the project or what day the teacher had them working on it in the classroom. The steps for finding a file by date created will differ depending upon the operating system but all are pretty similar. Here’s how it works in Windows:

- Open the Windows File Explorer.

- In the search box (or simply push Ctrl+F), type datemodified.

- A calendar will appear; select the date for when you believe the file was created or last modified.

- If it’s not in the drive you selected, reselect to search another server or attached drive.

If students don’t remember what date they created the file, start in the digital device’s “Recent” folder. This is found not only in the digital device being used but in many programs students use (like Office). This allows students to open recent work quickly without all the usual tedious steps.

Here’s one more way to search by date created: If you’re on a PC, click the Cortana icon in the taskbar and a list of recent activities shows up under “Pick up where you left off”. This includes the most recently saved files.

Did you delete it?

This question and the next one are unlikely to occur but do make a difference in rare instances. Sometimes, students delete the file by accident or because they think it’s an older version. It’s always worth checking the trash. If it’s in there, it’s easy to restore.

Where were you sitting?

This is only for classes that 1) don’t assign seats, or 2) move students around for whatever reason during class (maybe a computer is broken or the current seating doesn’t work that day). Have the student think back to where they were sitting the last time they worked on this project. They may have saved the file to that device’s local drive which means they must return to it and see if they can find it there.

This used to be a serious issue before cloud-based classroom accounts like Google Drive and One Drive became popular.

***

With the increased use of technology to deliver education, solving tech problems has become critical. If tech used for school only works because the teacher is available to solve a myriad of problems, well, it doesn’t work. It must be transferrable to wherever students wish to learn and students must learn to be their own problem-solvers. I’d love to hear what you do when files disappear in your classes.

–published first on TeachHUB

More on tech problem solving:

How to Teach Critical Thinking

How to Undelete with 2 Keystrokes

Jacqui Murray has been teaching K-18 technology for 30 years. She is the editor/author of over a hundred tech ed resources including a K-12 technology curriculum, K-8 keyboard curriculum, K-8 Digital Citizenship curriculum. She is an adjunct professor in tech ed, Master Teacher, webmaster for four blogs, an Amazon Vine Voice, CSTA presentation reviewer, freelance journalist on tech ed topics, contributor to NEA Today, and author of the tech thrillers, To Hunt a Sub and Twenty-four Days. You can find her resources at Structured Learning.