Constructivism is a student-centered philosophy that emphasizes hands-on learning and active participation in lessons. Constructivists believe that learning is an active process so the most effective way to learn is through discovery. With hands-on activities, learners actively create their own subjective representation of objective reality. Because new information is blended into prior knowledge, the result is – of course – subjective, heavily dependent upon the personal lens of each learner. That, in turn, is dependent upon their society, culture, past knowledge, personal experiences, and more.

Constructivism is a student-centered philosophy that emphasizes hands-on learning and active participation in lessons. Constructivists believe that learning is an active process so the most effective way to learn is through discovery. With hands-on activities, learners actively create their own subjective representation of objective reality. Because new information is blended into prior knowledge, the result is – of course – subjective, heavily dependent upon the personal lens of each learner. That, in turn, is dependent upon their society, culture, past knowledge, personal experiences, and more.

Learning is constructed, not acquired, and is based on the fullness of a person’s individual lifetime of learning. It is continuously tested as new ideas are added, either causing long-held beliefs to evolve or be replaced.

Constructivism is not a pedagogy or a theory. It is a mindset — a way of thinking used to guide learners.

Guiding Principles of Constructivism

- Constructivism 1) encourages students to use active techniques (such as experimentation and problem solving) to build their knowledge base and then reflect on and/or talk about how that is changing; and 2) encourages teachers to guide activities that address and/or build on student conceptions.

- Constructivism teaches students not the bullet points of a curriculum but how to learn by engaging in problem-solving, higher-order thinking, and collaboration.

- Constructivism’s cornerstones are similar to the concept of spiraling where students learn new material and then rewind to earlier learnings to review and integrate them. Constructivism’s rewind refers to student learning and experiences rather than previously-learned facts and figures.

- Constructivism works with any curricula because it isn’t one. It’s a learning philosophy like Habits of Mind or John Hattie’s Visible Learning (click for a discussion on those).

- Constructivism also works well with inquiry-based learning (click for more on inquiry-based teaching). Constructivism taps into and triggers student curiosity.

- In order to teach well, constructivism expects teachers to understand the assumptions students make to support their learning.

- To truly learn, students construct their own meaning, not memorize the “right” answers or regurgitate someone else’s meaning.

- Learning is incremental. Students don’t receive a data dump and walk away brilliant. They spend copious amounts of time learning, incorporating, and blending before understanding.

- Learning is iterative. Students constantly build new understanding on old knowledge.

- Constructivism builds on well-accepted education ideas like Jean Piaget’s belief that play is critical to learning, Marie Montessori’s teachings that exploration is essential to growth, and Lev Vygotsky’s theory that knowledge leads to further learning (the foundation for life-long learning).

- Constructivism is not a stimulus-response (as you would see in Behaviorism). It is an active response to the receipt of new information.

- Objective truth is unknowable. There are no absolute truths. Truth is dependent upon the learner’s personal reality. In a learning ecosystem, this puts the focus on evidence provided to support a claim rather than the memorization of rote facts.

Traditional teaching vs. Constructivism

- Traditional classes focus on teacher lecture; constructivism focuses on personal inquiry and class discussion.

- Traditional classes are teacher-centered while constructivist classes are student-centered.

- Traditional classes are teacher-paced (teachers decide when lessons are taught including quizzes) while constructivist classes are student-paced (dependent upon student investigation).

- Traditional classes tend to be less about higher-order thinking because of the importance placed on teacher lectures and overseeing. Constructivist classes insist students think about the lesson while engaging in problem-solving and critical thinking as a path to understanding.

- Traditional classes are based on teacher-prescribed facts (which could be mandated by state standards or curricula) where the constructivist approach expects students to compare new facts to the old and their personal experiences.

- Traditional classes include prescribed assessment where constructivism calls for the elimination of grades and standardized testing. Assessment becomes part of the learning process, expecting students to judge their own progress.

Myths

Because constructivism doesn’t align with the common education philosophies and thus isn’t taught in depth even in teacher training programs, it’s not surprising that there are misunderstandings about what it is and how it is unpacked in the education ecosystem. Here are some popular myths that prove untrue in the constructivist classroom:

Teachers can’t answer questions: This refers to the idea that students are expected to be problem-solvers and find answers based on their own experience. This forgets that constructivism asks teachers to share their educated ideas and that becomes part of the student knowledge base, incorporated into future learning. The expectation is that students build their knowledge based on multiple inputs (which includes class teaching).

Constructivism replaces teachers with guides: Not really. Constructivism does not dismiss the active role of the teacher or the value of expert knowledge. Rather, it modifies that role, expecting teachers to help students construct knowledge but without demanding they reproduce a series of rote facts.

Knowledge is subjective: For this one, we’ll have to stipulate that all knowledge is subjective and heavily-dependent upon a learner’s experiences. For example, most agree a panther’s color is black, but for some, it isn’t. Black is the absence of color (or the blend of all colors), not a color itself. When someone asked Pierre-Auguste Renoir (a prominent Impressionist painter) what color a black panther was, he replied:

“A black panther is actually a melanistic leopard or jaguar, the result of an excess of melanin in their skin …”

So which answer is right — the common one or Renoir’s? Or both?

Education applications

If this sounds confusing, Let me de-muddle it for you. Look at all these ways constructivism is already blended successfully into most lesson plans:

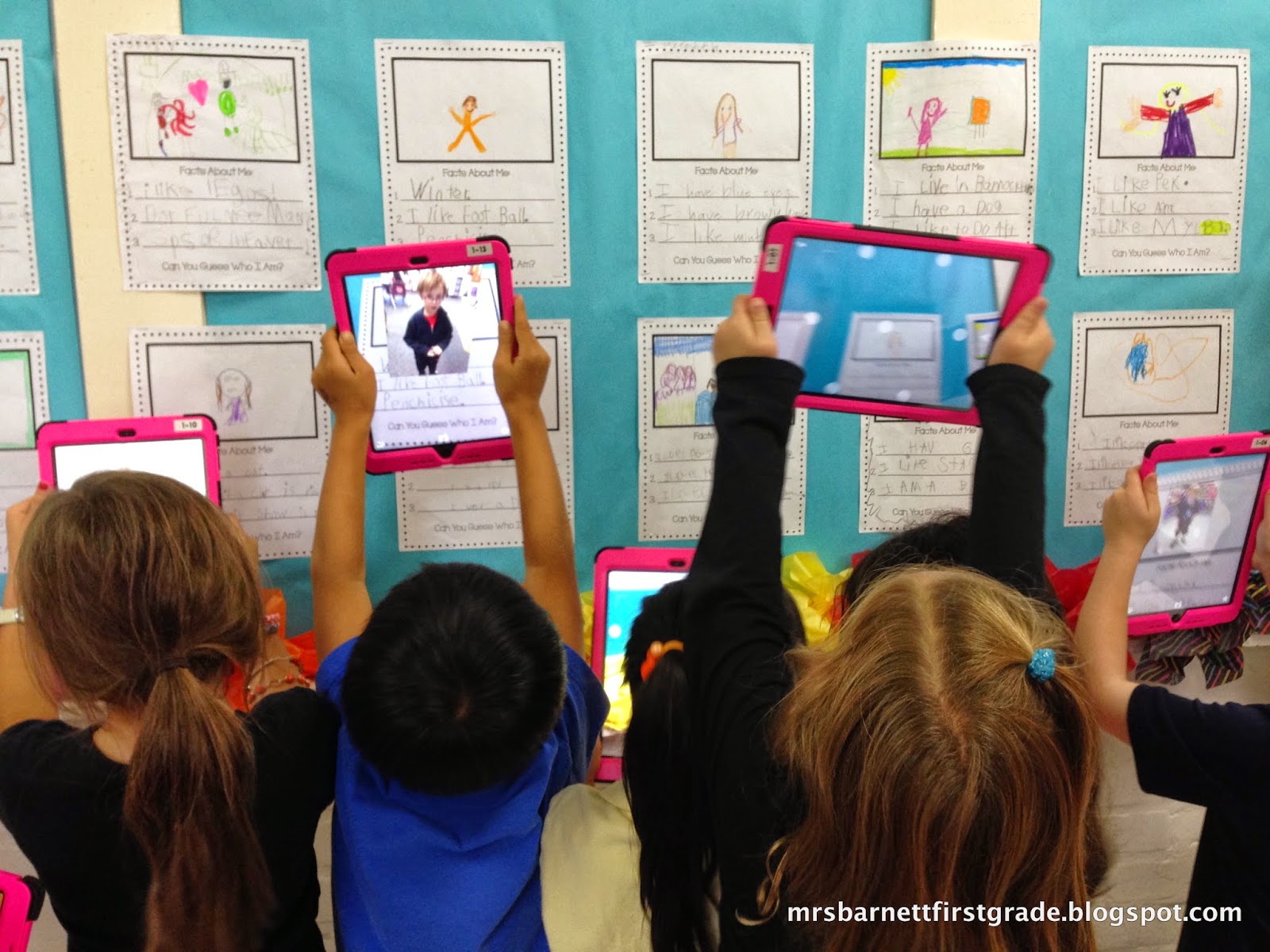

- role-playing: See the world through the eyes of historical figures.

- debate: Gain perspective on differing views in politics, philosophy, or policy.

- experimentation: Perform individual or group experiments in support of a lesson plan, followed by class discussion.

- research projects: Research a topic and present findings to class (like the popular Genius Hour).

- cooperative learning: Work in small or large groups to gain exposure to different perspectives.

- internships: Engage in community activities to determine how class theory meets the real world.

- community service: Offer student skills in support of community needs to gain understanding of how they fit.

- field trip: See the real-world context to class concepts such as farming, a factory, or local government in action.

***

In any given class, how well a lesson plan works depends on the students. If you are frustrated because your best teaching falls on bored ears, try a different approach, like constructivism.

More on education pedagogies

What is the VARK model of Student Learning?

Is Whole Brain Teaching Right for Me?

Jacqui Murray has been teaching K-18 technology for 30 years. She is the editor/author of over a hundred tech ed resources including a K-12 technology curriculum, K-8 keyboard curriculum, K-8 Digital Citizenship curriculum. She is an adjunct professor in tech ed, Master Teacher, webmaster for four blogs, an Amazon Vine Voice, CSTA presentation reviewer, freelance journalist on tech ed topics, contributor to NEA Today and author of the tech thrillers, To Hunt a Sub and Twenty-four Days. You can find her resources at Structured Learning.