Teaching used to be based on textbooks used by millions nation- or worldwide. They took an entire school year to finish leaving little time for curiosity or creativity. Some subjects still do fine with that approach because their pedagogy varies little year-to-year.

Teaching used to be based on textbooks used by millions nation- or worldwide. They took an entire school year to finish leaving little time for curiosity or creativity. Some subjects still do fine with that approach because their pedagogy varies little year-to-year.

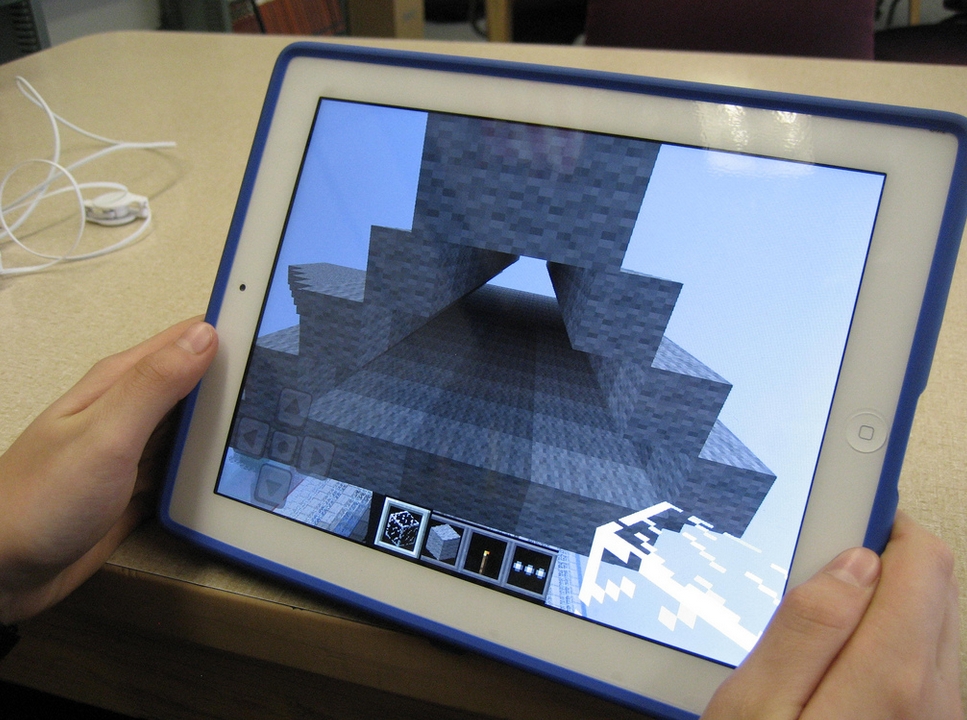

In my classes, though, that’s changing. I no longer limit myself to the contents of a textbook written years, sometimes a decade, ago. Now, I’m likely to cobble together lesson plans from a variety of time-sensitive and differentiated material. Plus, I commonly expect students to dig deeper into class conversations, think critically about current event connections, and gain perspective by comparing lesson materials to world cultures. That, of course, usually ends up not in a library but on the Internet.

Before I set them loose in the virtual world, though, I teach them the “rules of the Internet road” because make no mistake: There are rules. The Internet’s Wild West days are fast disappearing, replaced with the security offered by abiding to a discrete set of what’s commonly referred to as “digital rights and responsibilities“. It boils down to a simple maxim:

With the right to discover knowledge comes the responsibility to behave well while doing so.

The privileges and freedoms extended to digital users who type a URL into a browser or click a link in a PDF or scan a QR Code require that they bear the responsibility to keep the virtual library a safe and healthy environment for everyone.

Digital Rights

Most people if asked could easily name the benefits of the Internet:

- Everyone can speak their mind knowing they’ll find like-minded individuals.

- Privacy is ensured by its vastness. Think about living in the desert — who could ever find you there? It’s that sort of vastness.

- As a creator, you can expose a world of people to your creations to purchase or just spread the word.

- You can find any information you want just by typing in search terms and slogging through the multitude of hits.

- You can create an online persona that doesn’t include your faults, lousy personality, or mistakes.

These rights are so pervasive to our daily activities that many consider them to be inalienable, not unlike those laid out in the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. To these folks, disconnecting people from the Internet is a violation of international law and tramples all over an individual’s human rights.

Digital Responsibilities

But there are two faces to this digital coin: Inalienable or not, they require great responsibilities. Some think the Internet’s lawlessness (because no world authority holds legal authority over the world wide web) precludes cultural norms like kindness, morality, and ethics. After all, if you purchase porn from a third-world nation where it’s legal to sell, who’s going to enforce what law?

That’s where I teach my students that with rights come responsibilities. Think of the Internet as having comparable expectations to a neighborhood:

- Act the same online as you’d act in your neighborhood.

- Don’t share personal information. Don’t ask others for theirs. Respect their need for privacy.

- Be aware of your surroundings. Know where you are in cyberspace. Act accordingly.

- Just as in your community, if you are kind to others, they will be kind to you.

- Don’t think anonymity protects you—it doesn’t. You are easily found with an IP address. Discuss what that is.

- Share your knowledge. Collaborate and help others online.

Information Security Education and Awareness posits these Ten Commandments for computer use:

- One shall not use a computer to harm other people.

- One shall not interfere with other’s computer work.

- One shall not snoop around in another ‘s computer files [and will keep one’s own data safe from hackers].

- One shall not use a computer to steal [or plagiaurze].

- One shall not use a computer to bear false witness [or to falsify one’s own identity].

- One shall not copy or use any materials for which one has not paid.

- One shall not use other’s computer resources without authorization or proper compensation.

- One shall not appropriate other’s intellectual output [and will legally download all material like music and videos].

- One shall think about social consequences of the program written or of the system designed.

- One shall always use a computer in ways that respect one’s fellow humans [and report bullying, harassing, and identify theft when possible].

… and eight “don’ts” for computer users:

- Do not use computers to harm other users.

- Do not use computers to steal other’s information.

- Do not access files without the permission of the owner.

- Do not disrespect copyright laws and policies.

- Do not disrespect the privacy of others.

- Do not use other’s computer resources without their permission.

- Do not write your User Id and Passwords where others can find it.

- Do not intentionally use computers to retrieve or modify the information of others.

Knowing this, consider three of the great threats to the safe and equitable use of the Internet:

- plagiarism

- hoaxes

- spam

Plagiarism

The responsibility to use all data, files, and information from the Internet legally, wisely, and safely means: Don’t plagiarize. Always credit the creator. In general terms, you must cite sources for:

- facts not commonly known or accepted

- exact words and/or unique phrases

- reprints of diagrams, illustrations, charts, pictures, or other visual materials

- opinions that support research

Most students are well-versed in the illegality of stealing someone’s online words but plagiarism extends to all forms of media — images, photos, audio files, videos, and more. Few students make those connections. In fact, they’re likely to think if a picture is online, it’s free.

Hoaxes

It’s tempting to believe that everything online is legitimate yet it’s easy to fake a picture with programs like Photoshop. Look at this picture of President Roosevelt crossing a river on a moose*.

This happens so often, even by amateurs, that they are no longer legal in courts of law.

When trying to differentiate between legitimate information and hoaxes, consider these questions:

- Is the author an expert or a third grader?

- Is the information current or dated?

- Is the data neutral or biased?

- Is it believable (could a man cross a river on a moose)?

Look at these sites and decide if they’re hoaxes — and why:

Spam

Spam is defined as “irrelevant or inappropriate messages sent on the Internet to a large number of recipients.” Today, that not only includes annoying marketing emails but phishing (sending emails purporting to be from reputable companies) and spoofing (the forgery of an email header so that the message appears to be from someone legitimate). These are designed solely to trick you into giving out personal information or install malware on your computer that gives others access to it.

Here are seven tips for avoiding spam:

- Don’t give out your email address in public forums. If you must, write it as johndoe at verizon dot net. That will trick trolls but not humans.

- Never respond to spam.

- Always preview email before downloading.

- Never open attachments unless you’re sure they’re safe (i.e., from someone you know).

- Use an email filter.

- If spam slips through, block it through the tools available in your email program.

- When you purchase online, beware of receipt dialogue boxes with checkboxes already filled in.

The most important part of this article: Accessing the Internet includes behavioral expectations. Teach this as soon as students visit the Internet (probably kindergarten). Reteach it every year. Add details that are age-appropriate. Never consider your job done until your students and children can cross that virtual road safely, after looking both ways for dangerous digital traffic.

*The Roosevelt photo is in the public domain because it was created more than seventy years after the death of its creator. That’s why I didn’t cite it.

Jacqui Murray has been teaching K-18 technology for 30 years. She is the editor/author of over a hundred tech ed resources including a K-12 technology curriculum, K-8 keyboard curriculum, K-8 Digital Citizenship curriculum. She is an adjunct professor in tech ed, Master Teacher, webmaster for four blogs, an Amazon Vine Voice, CSTA presentation reviewer, freelance journalist on tech ed topics, contributor to NEA Today, and author of the tech thrillers, To Hunt a Sub and Twenty-four Days. You can find her resources at Structured Learning.

3 thoughts on “Teaching Digital Rights and Responsibilities”

Comments are closed.