Category: Problem solving

Ten Tech Problem-Solving Tips You Don’t Want to Miss

Here are the top ten problem-solving tips according to Ask a Tech Teacher readers:

Here are the top ten problem-solving tips according to Ask a Tech Teacher readers:

- Tech Tip #108: Got a Tech Problem? Google It!

- What to do when your Computers Don’t Work

- 25 Techie Problems Every Student Can Fix–Update

- How to Teach Students to Solve Problems

- I Can Solve That Problem…

- Let Students Learn From Failure

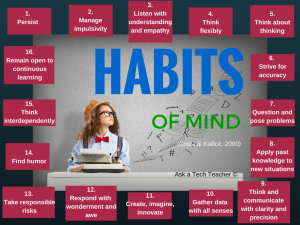

- Let’s Talk About Habits of Mind

- Computer Shortkeys That Streamline Your Day

- #81: Problem Solving Board

- 5 Ways to Cure Technophobia in the Classroom

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

Hour of Code: Program Shortkeys

Creating a shortkey for a program will quickly become a favorite with your students. I use it for the snipping tool–because we use that a lot in class–but you can create one for any program you use a lot. Then I discovered how to create a shortkey for it:

Creating a shortkey for a program will quickly become a favorite with your students. I use it for the snipping tool–because we use that a lot in class–but you can create one for any program you use a lot. Then I discovered how to create a shortkey for it:

- Go to Start

- Right click on the desired program

- Select ‘properties’

- Click in ‘shortcut’

- Push the key combination you want to use to invoke the snipping tool. In my case, I used Ctrl+Alt+S

- Save

Here’s a video to show you:

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

Hour of Code: Minecraft Review

Every week, I share a website that inspired my students. This one is perfect for Hour of Code. Make yourself a hero for an hour:

Age:

Grades 3-8 (or younger, or older)

Topic:

Problem-solving, critical thinking, building

Address:

Review:

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

58 Hour of Code Suggestions by Grade Level

Here are ideas of apps and websites that teachers in my PLN used successfully in the past during Hour of Code:

Kindergarten

Kindergarten

Start kindergartners with problem solving. If they love Legos, they’ll love coding

- BotLogic–great for Kindergarten and youngers

- Code–learn to code, for students

- Daisy the Dinosaur—intro to programming via iPad

- How to train your robot–a lesson plan from Dr. Techniko

- Kodable--great for youngers–learn to code before you can read

- Move the Turtle–programming via iPad for middle school

- Primo–a wooden game, for ages 4-7

- Program a human robot (unplugged)

- Scratch Jr.

1st Grade

- Code–learn to code, for students

- Hopscotch–programming on the iPad

- Primo–a wooden game, for ages 4-7

- Scratch Jr.

- Tynker

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

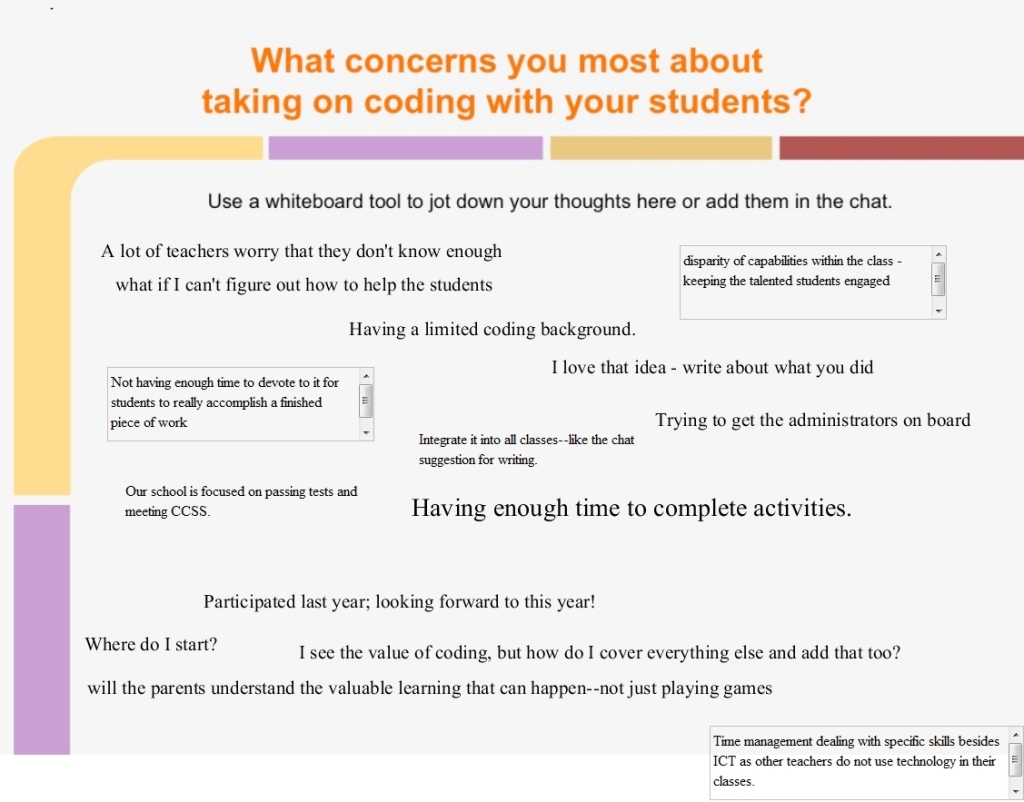

Hour of Code–Why Not

I took a Classroom 2.0 Live webinar last year on rolling out the Hour of Code in the classroom. There were so many great things about that webinar, but one I’ll share today is why teachers DON’T participate in Hour of Code. Here are what the webinar participants said:

How about you? Why are you NOT doing Hour of Code?

How about you? Why are you NOT doing Hour of Code?

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

Hour of Code–the Series

Coding–that mystical geeky subject that confounds students and teachers alike. Confess, when you think of coding, you see:

…when you should see

December 7-13, Computer Science Education will host the Hour Of Code–a one hour introduction to coding, programming, and why students should love it. It’s designed to demystify “code” and show that anyone can learn the basics to be a maker, a creator, and an innovator.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

Let Students Learn From Failure

Too often, students–and teachers–believe learning comes from success when in truth, it’s as likely to be the product of failure. Knowing what doesn’t work is a powerful weapon as we struggle to think critically about the myriad issues along our path to college and/or career. As teachers, it’s important we reinforce the concept that learning has many faces.

Here are ten ways to teach through failure:

Use the Mulligan Rule

Use the Mulligan Rule

What’s the Mulligan Rule? Any golfers? A mulligan in golf is a do-over. Blend that concept into your classroom. Common Core expect students to write-edit-resubmit. How often do you personally rewrite an email before sending? Or revise instructions before sharing? Or have ‘buyer’s remorse’ after a purchase and wish you could go back and make a change? Make that part of every lesson. After submittal, give students a set amount of time to redo and resubmit their work. Some won’t, but those who do will learn much more by the process.

Don’t define success as perfection

When you’re discussing a project or a lesson, don’t define it in terms of checkboxes or line items or 100% accuracy. Think about your favorite book. Is it the same as your best friend’s? How about the vacation you’re planning–would your sister pick that dream location? Education is no different. Many celebrated ‘successful’ people failed at school because they were unusual thinkers. Most famously: Bill Gates, who dropped out of college because he believed  he could learn more from life than professors.

he could learn more from life than professors.

Education pedagogists categorize these sorts of ideas as higher-order thinking and Habits of Mind–traits that contribute to critical thinking, problem solving, and thriving. These are difficult to quantify on a report card, but critical to life-long success. Observe students as they work. Notice their risk-taking curiosity, how they color outside the lines. Anecdotally assess their daily efforts and let that count as much as a summative exam that judges a point in time.

Let students see you fail

One reason lots of teachers keep the same lesson plans year-to-year is they are vetted. The teacher won’t be surprised by a failure or a question they can’t answer. Honestly, this is a big reason why many eschew technology: Too often, it fails at just that critical moment.

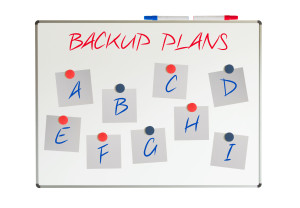

Revise your mindset. Don’t hide your failures from students. Don’t apologize. Don’t be embarrassed or defeated. Show them how you recover from failure. Model the steps you take to move to Plan B, C, even X. Show your teaching grit and students will understand that, too, is what they’re learning: How to recover from failure.

Share strategies for problem solving

Problems are inevitable. Everyone has them. What many people DON’T have is a strategy to address them. Share these with students. The Common Core Standards for Mathematical Practice is a good starting point. Mostly, they boil down to these simple ideas:

- Act out a problem

- Break problem into parts

- Draw a diagram

- Guess and check

- Never say ‘can’t’

- See patterns

- Notice the forest and the trees

- Think logically

- Distinguish relevant from irrelevant info

- Try, fail, try again

- Use what has worked in the past

Post these on the classroom wall. When students have problems, suggest they try a strategy from this list, and then another, and another. Eventually, the problem will resolve, the result of a tenacious, gritty attack by an individual who refuses to give up.

Exult in problems

If you’re geeky, you love problems, puzzles, and the maze that leads from question to answer. It doesn’t intimidate or frighten you, it energizes you. Share that enthusiasm with students. They are as likely to meet failure as success in their lives; show them your authentic, granular approach to addressing that eventuality.

Assess grit

Success isn’t about right and wrong. More often, it’s about grit–tenacity, working through a process, and not giving up when failure seems imminent. Statistically, over half of people say they ‘succeeded’ (in whatever venture they tried) not by being the best in the field but because they were the last man standing.

Integrate that into your lessons. Assess student effort, their attention to detail, their ability to transfer knowledge from earlier lessons to this one, their enthusiasm for learning, how often they tried-failed-retried, and that they completed the project. Let students know they will be evaluated on those criteria more than the perfection of their work.

Let students teach each other

There are many paths to success. Often, what works for one person is based on their perspective, personal history, and goals. This is at the core of differentiation: that we communicate in multiple ways–visually, orally, tactally–in an effort to reach all learning styles.

Even so, students may not understand. Our failure to speak in a language they understand will become their failure to learn the material. Don’t let that happen. Let students be the teachers. They often pick a relationship or comparison you wouldn’t think of. Let students know that in your classroom, brainstorming and freedom of speech are problem solving strategies.

Don’t be afraid to move the goalposts

Even if it’s in the middle of a lesson. That happens all the time in life and no one apologizes, feels guilty, or accommodates your anger. When you teach a lesson, you constantly reassess based on student progress. Do the same with assessment.

But make it fair. Let students know the changes are rooted in your desire that they succeed. If you can’t make that argument, you probably shouldn’t make the change.

Success is as much serendipity as planning

Think of Velcro and post-it notes–life-changing products resulting from errors. They surprised their creators and excited the world. Keep those possibilities available to students.

Don’t reward speed

Often, students who finish first are assigned the task of helping neighbors or playing time-filler games. Finishing early should not be rewarded. Or punished. Sometimes it means the student thoroughly understood the material. Sometimes it means they glossed over it. Students are too often taught finishing early is a badge of honor, a mark of their expertise. Remove that judgment and let it be what it is.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

6 Tech Best Practices for New Teachers

A study released last year by the National Council on Teacher Quality found that nearly half of the nation’s teacher training programs failed to insure that their candidates were STEM-capable. That means new teachers must learn how to teach science, technology, engineering and math on-the-job. Knowing that, there are six Best Practices teachers in the trenches suggest for integrating technology into classroom instruction:

Digital Citizenship

Digital Citizenship

Many schools now provide digital devices for students, often a Chromebook or an iPad. Both are great devices, but represent a sea change from the Macs and PCs that have traditionally been the device-of-choice in education. While I could spend this entire article on that topic, one seminal difference stands out: Where PCs and Macs could be used as a closed system via software, materials saved to the local drive, and native tools, Chromebooks and iPads access the internet for everything (with a few exceptions) be it learning, publishing, sharing, collaborating, or grading. There’s no longer an option to hide students from the online world, what is considered by many parents a dangerous place their children should avoid. In cyberspace, students are confronted often–if not daily–with questions regarding cyberbullying, digital privacy, digital footprints, plagiarism, and more.

The question is: Who’s teaching students how to thrive in this brave new world? Before you move on to the next paragraph, think about that in your circumstance. Can you point to the person responsible for turning your students into good digital citizens? When third grade students use the internet to research a topic, do they know how to do that safely and legally?

When asked, most educators shrug and point at someone else. But it turns out too often, no one is tasked with providing that knowledge.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

Tech Tip #115: Three-click Rule

As a working technology teacher, I get hundreds of questions from parents about their home computers, how to do stuff, how to solve problems. Each Tuesday, I’ll share one of those with you. They’re always brief and always focused. Enjoy!

Q: Some websites/blogs are confusing. I click through way too many options to get anything done. What’s with that?

A: I hadn’t put a lot of thought to this until I read a discussion on one of my teacher forums about the oft-debunked-and-oft-followed 3-click rule made popular by Web designer Jeffrey Zeldman in his book, “Taking Your Talent to the Web.”. This claims ‘that no product or piece of content should ever be more than three clicks away from your Web site’s main page’.

This is true with not just programming a website, but teaching tech to students. During my fifteen years of teaching tech, I’ve discovered if I keep the geeky stuff to a max of 2-3 steps, students remember it, embrace it, and use it. More than three steps, I hear the sound of eyes glazing over.

Whether you agree with the ‘rule’ or not, it remains a good idea to make information easy and quick to find. Readers have a short attention span. Same is true of students.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

Tech Tip #108: Got a Tech Problem? Google It!

As a working technology teacher, I get hundreds of questions from parents about their home computers, how to do stuff, how to solve problems. Each Tuesday, I’ll share one of those with you. They’re always brief and always focused. Enjoy!

As a working technology teacher, I get hundreds of questions from parents about their home computers, how to do stuff, how to solve problems. Each Tuesday, I’ll share one of those with you. They’re always brief and always focused. Enjoy!

Q: Sometimes, I just can’t remember how to accomplish a task. Often, I know it’s simple. Maybe I’ve done it before–or even learned it before–and it’s lost in my brain. What do I do?

A: One of the best gifts I have for students and colleagues alike is how to solve this sort of problem. Before you call your IT guy, or the tech teacher, or dig through those emails where someone sent you the directions, here’s what you do:

Google it.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More