Category: Critical thinking

Hour of Code Website and App Suggestions for K-8

Here are ideas of apps and websites that teachers in my PLN used successfully in the past during Hour of Code:

Kindergarten

Kindergarten

Start kindergartners with problem solving. If they love Legos, they’ll love coding

- BotLogic–great for Kindergarten and youngers

- Code–learn to code, for students

- How to train your robot–a lesson plan from Dr. Techniko

- Kodable--great for youngers–learn to code before you can read

Primo–a wooden game, for ages 4-7

Primo–a wooden game, for ages 4-7- Program a human robot (unplugged)

- Scratch Jr.

1st Grade

- Code–learn to code, for students

- Espresso Coding–for youngers

- Foos–app or desktop; K-1

- Hopscotch–programming on the iPad

- Primo–a wooden game, for ages 4-7

- Scratch Jr.

- Tynker

Share this:

Hour of Code–What is it?

Coding–that mystical geeky subject that confounds students and teachers alike. Confess, when you think of coding, you see:

…when you should see

December 5-11, Computer Science Education will host the Hour Of Code–a one-hour introduction to coding, programming, and why students should love it. It’s designed to demystify “code” and show that anyone can learn the basics to be a maker, a creator, and an innovator.

Share this:

Hour of Code–Is it the right choice?

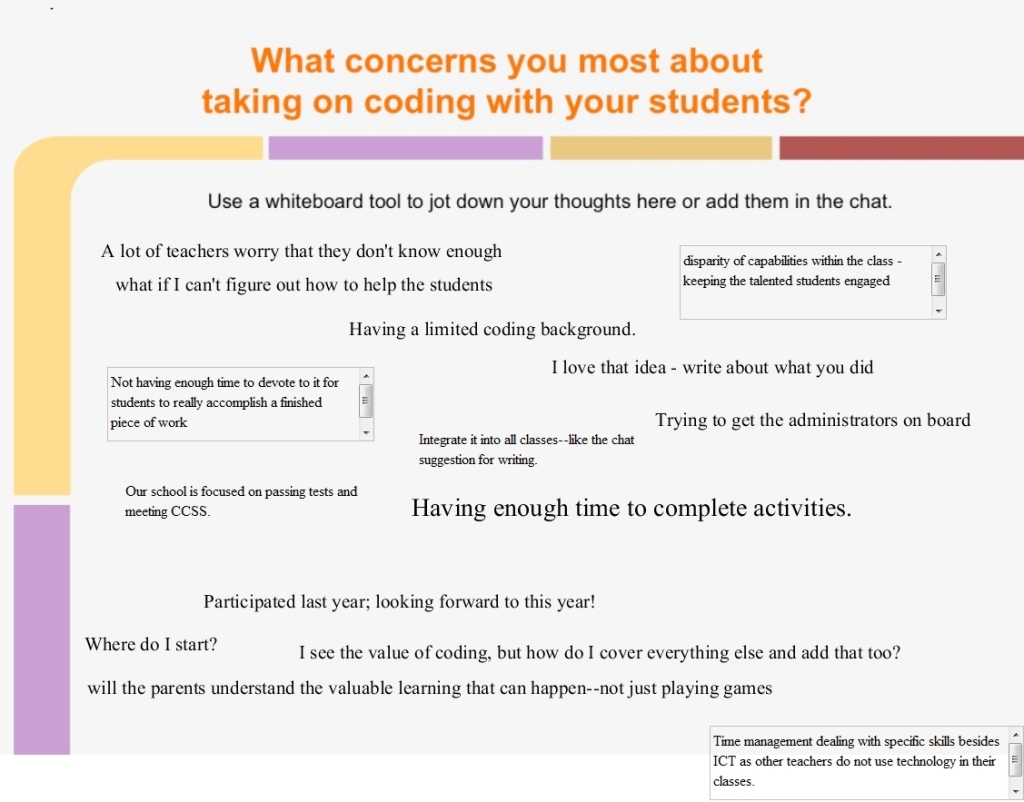

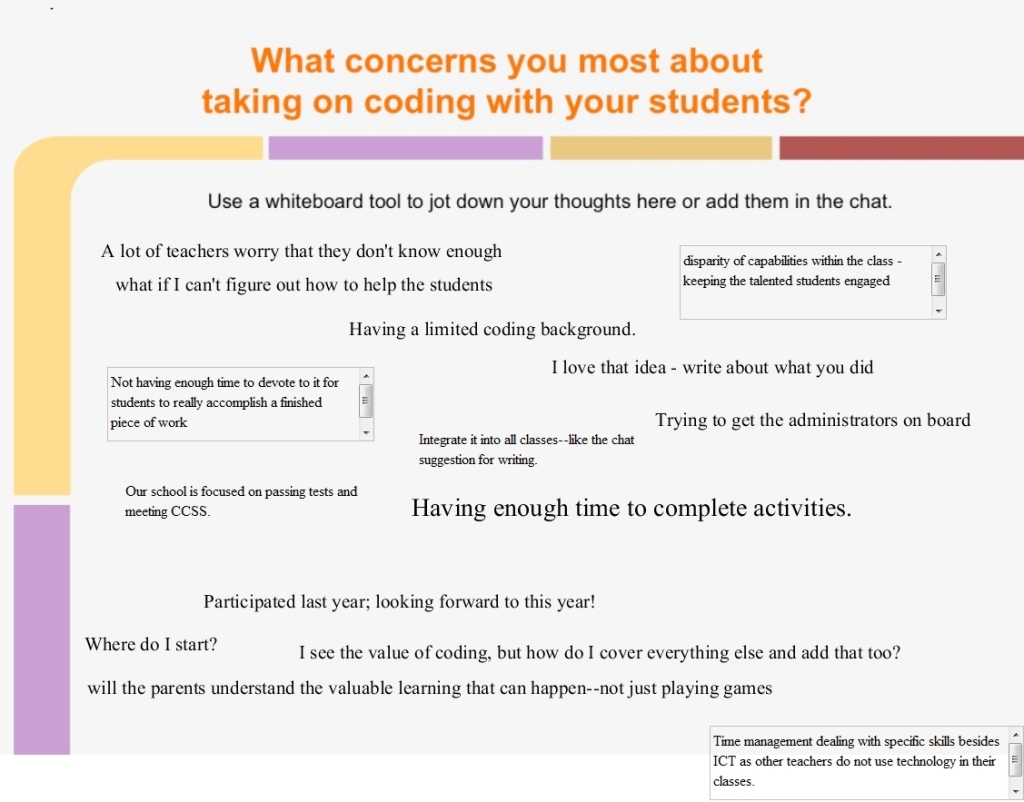

I took a Classroom 2.0 Live webinar last year on rolling out the Hour of Code in the classroom. There were so many great things about that webinar, but one I’ll share today is why teachers DON’T participate in Hour of Code. Here are what the webinar participants said:

How about you? Why are you NOT doing Hour of Code?

How about you? Why are you NOT doing Hour of Code?

Stay tuned for these Hour of Code articles on how to present coding in your classroom:

- Hour of Code: What is it? (November 15th)

- Hour of Code Suggestions by Grade Level (November 16th)

- 10 Projects to Kickstart Hour of Code (November 17th)

Share this:

7 Innovative Writing Methods for Students

Knowledge is meant to be shared. That’s what writing is about–taking what you know and putting it out there for all to see. When students hear the word “writing”, most think paper-and-pencil, maybe word processing, but that’s the vehicle, not the goal. According to state and national standards (even international), writing is expected to “provide evidence in support of opinions”, “examine complex ideas and information clearly and accurately”, and/or “communicate in a way that is appropriate to task, audience, and purpose”. Nowhere do standards dictate a specific tool be used to accomplish the goals.

In fact, the tool students select to share knowledge will depend upon their specific learning style. Imagine if you–the artist who never got beyond stick figures–had to draw a picture that explained the nobility inherent in the Civil War. Would you feel stifled? Would you give up? Now put yourself in the shoes of the student who is dyslexic or challenged by prose as they try to share their knowledge.

When you first bring this up in your class, don’t be surprised if kids have no idea what you’re talking about. Many students think learning starts with the teacher talking and ends with a quiz. Have them take the following surveys:

- North Carolina State University’s learning style quiz

Both are based on the Theory of Multiple Intelligences, Howard Gardner’s iconic model for mapping out learning modalities such as linguistic, hands-on, kinesthetic, math, verbal, and art. Understanding how they learn explains why they remember more when they write something down or read their notes rather than listening to a lecture. If they learn logically (math), a spreadsheet is a good idea. If they are spatial (art) learners, a drawing program is a better choice.

Share this:

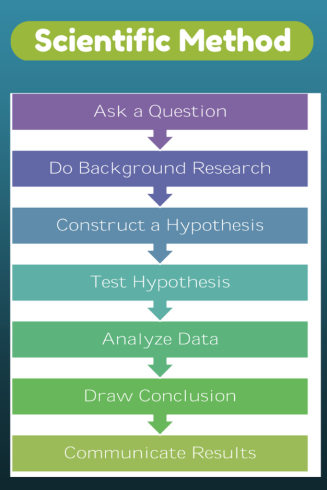

Keyboarding and the Scientific Method

Convincing students–and teachers–of the importance of keyboarding can be daunting. Youngers find it painful (trying to find those 26 alphabet keys) and olders think their hunt-and-peck approach is just fine. Explaining why keyboarding is critical to their long-range goals is often an exercise in futility if they haven’t yet experienced it authentically so I’ve resorted to showing–let them see for themselves why they want to become fast and accurate typists. To do this, I rely on a system they already know (or will be learning): the Scientific Method.

Convincing students–and teachers–of the importance of keyboarding can be daunting. Youngers find it painful (trying to find those 26 alphabet keys) and olders think their hunt-and-peck approach is just fine. Explaining why keyboarding is critical to their long-range goals is often an exercise in futility if they haven’t yet experienced it authentically so I’ve resorted to showing–let them see for themselves why they want to become fast and accurate typists. To do this, I rely on a system they already know (or will be learning): the Scientific Method.

Let me stop here and point out that there are many versions of the scientific method. Use the one popular at your school. The upcoming steps easily adapt to the pedagogy your science teacher recommends.

I start with a general discussion of this well-accepted approach to decision making and problem-solving. If students have discussed it in class, I have them share their thoughts. We will use it to address the question:

Is handwriting or keyboarding faster?

I post each step on the Smartscreen or whiteboard and show students how our experiment will work:

- Ask a question: Is handwriting or keyboarding faster?

- Do background research: Discuss why students think they handwrite faster/slower than they type. Curious students might even research the topic by Googling, Is keyboarding faster than handwriting?

- Construct a hypothesis: Following the research, student states her/his informed conclusion: i.e.: Fifth graders in Mr. X’s class handwrite faster than they type.

- Test hypothesis: Do an experiment to see if handwriting or typing is faster. Pass out a printed page from a book students are reading in class. Have them 1) handwrite it for three minutes, and then 2) type it for the same length of time. Each time, calculate the speed in words-per-minute.

- Analyze data: Compare student personal handwriting speed to their typing speed. Which is faster? Discuss data. Why do some students type faster than they write and others slower? Or the reverse? What problems were faced in handwriting for three-five minutes:

- pencil lead broke

- eraser was missing

- hand got tired

- it got boring

Each student compares their results to classmates and to other grade levels. What was different? Or the same?

- Draw conclusions: Each student determines what can be decided based on their personal test results. Did they type faster or slower? Did this change from last year’s results? Did some classmates type faster than they handwrote? Did most students by a certain grade level type faster than they write?

- Communicate results: Share results with other classes and other grade levels. At what grade level do students consistently type faster than they handwrite? In my classes, fourth graders write and type at about the same speed (22-28 wpm) and fifth graders generally type faster than they write. Are students surprised by the answer?

Share this:

10 Bits of Wisdom I Learned From a Computer

Life is hard, but help is all around us. The trick is to take your learning where you find it. In my case, as a technology teacher, it‘s from computers. A while ago I posted four lessons I learned from computers:

Life is hard, but help is all around us. The trick is to take your learning where you find it. In my case, as a technology teacher, it‘s from computers. A while ago I posted four lessons I learned from computers:

- Know when your RAM is full

- You Can‘t Go Faster Than Your Processor Speed

- Take Shortcuts When You Can

- Be Patient When You‘re Hourglassing

I got a flood of advice from readers about the geeky lessons they got from computers. See which you relate to:

#5: Go offline for a while

#5: Go offline for a while

We are all getting used to–even addicted to–that online hive mind where other voices with thoughts and opinions are only a click away. Who among us hasn’t wasted hours on Facebook, Twitter, blogs–chatting with strangers or virtual friends ready to commiserate and offer advice. It’s like having a best friend who’s always available.

But while your back is turned, the real world is changing. Once in a while, disconnect from your Facebook, Twitter, Instagram–even your blogmates. Re-acquaint yourself with the joys of facial expressions, body language, and that tone of voice that makes the comment, “Yes, I’d be happy to help” sincere or snarky. Engage your brain in a more intimate and viscerally satisfying world.

Share this:

58 Hour of Code Suggestions by Grade Level

Here are ideas of apps and websites that teachers in my PLN used successfully in the past during Hour of Code:

Kindergarten

Kindergarten

Start kindergartners with problem solving. If they love Legos, they’ll love coding

- BotLogic–great for Kindergarten and youngers

- Code–learn to code, for students

- Daisy the Dinosaur—intro to programming via iPad

- How to train your robot–a lesson plan from Dr. Techniko

- Kodable--great for youngers–learn to code before you can read

- Move the Turtle–programming via iPad for middle school

- Primo–a wooden game, for ages 4-7

- Program a human robot (unplugged)

- Scratch Jr.

1st Grade

- Code–learn to code, for students

- Hopscotch–programming on the iPad

- Primo–a wooden game, for ages 4-7

- Scratch Jr.

- Tynker

Share this:

Hour of Code–Why Not

I took a Classroom 2.0 Live webinar last year on rolling out the Hour of Code in the classroom. There were so many great things about that webinar, but one I’ll share today is why teachers DON’T participate in Hour of Code. Here are what the webinar participants said:

How about you? Why are you NOT doing Hour of Code?

How about you? Why are you NOT doing Hour of Code?

Share this:

Hour of Code–the Series

Coding–that mystical geeky subject that confounds students and teachers alike. Confess, when you think of coding, you see:

…when you should see

December 7-13, Computer Science Education will host the Hour Of Code–a one hour introduction to coding, programming, and why students should love it. It’s designed to demystify “code” and show that anyone can learn the basics to be a maker, a creator, and an innovator.

Share this:

Let Students Learn From Failure

Too often, students–and teachers–believe learning comes from success when in truth, it’s as likely to be the product of failure. Knowing what doesn’t work is a powerful weapon as we struggle to think critically about the myriad issues along our path to college and/or career. As teachers, it’s important we reinforce the concept that learning has many faces.

Here are ten ways to teach through failure:

Use the Mulligan Rule

Use the Mulligan Rule

What’s the Mulligan Rule? Any golfers? A mulligan in golf is a do-over. Blend that concept into your classroom. Common Core expect students to write-edit-resubmit. How often do you personally rewrite an email before sending? Or revise instructions before sharing? Or have ‘buyer’s remorse’ after a purchase and wish you could go back and make a change? Make that part of every lesson. After submittal, give students a set amount of time to redo and resubmit their work. Some won’t, but those who do will learn much more by the process.

Don’t define success as perfection

When you’re discussing a project or a lesson, don’t define it in terms of checkboxes or line items or 100% accuracy. Think about your favorite book. Is it the same as your best friend’s? How about the vacation you’re planning–would your sister pick that dream location? Education is no different. Many celebrated ‘successful’ people failed at school because they were unusual thinkers. Most famously: Bill Gates, who dropped out of college because he believed  he could learn more from life than professors.

he could learn more from life than professors.

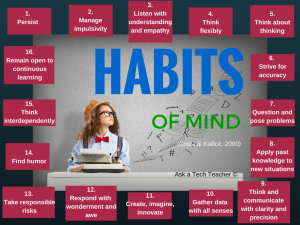

Education pedagogists categorize these sorts of ideas as higher-order thinking and Habits of Mind–traits that contribute to critical thinking, problem solving, and thriving. These are difficult to quantify on a report card, but critical to life-long success. Observe students as they work. Notice their risk-taking curiosity, how they color outside the lines. Anecdotally assess their daily efforts and let that count as much as a summative exam that judges a point in time.

Let students see you fail

One reason lots of teachers keep the same lesson plans year-to-year is they are vetted. The teacher won’t be surprised by a failure or a question they can’t answer. Honestly, this is a big reason why many eschew technology: Too often, it fails at just that critical moment.

Revise your mindset. Don’t hide your failures from students. Don’t apologize. Don’t be embarrassed or defeated. Show them how you recover from failure. Model the steps you take to move to Plan B, C, even X. Show your teaching grit and students will understand that, too, is what they’re learning: How to recover from failure.

Share strategies for problem solving

Problems are inevitable. Everyone has them. What many people DON’T have is a strategy to address them. Share these with students. The Common Core Standards for Mathematical Practice is a good starting point. Mostly, they boil down to these simple ideas:

- Act out a problem

- Break problem into parts

- Draw a diagram

- Guess and check

- Never say ‘can’t’

- See patterns

- Notice the forest and the trees

- Think logically

- Distinguish relevant from irrelevant info

- Try, fail, try again

- Use what has worked in the past

Post these on the classroom wall. When students have problems, suggest they try a strategy from this list, and then another, and another. Eventually, the problem will resolve, the result of a tenacious, gritty attack by an individual who refuses to give up.

Exult in problems

If you’re geeky, you love problems, puzzles, and the maze that leads from question to answer. It doesn’t intimidate or frighten you, it energizes you. Share that enthusiasm with students. They are as likely to meet failure as success in their lives; show them your authentic, granular approach to addressing that eventuality.

Assess grit

Success isn’t about right and wrong. More often, it’s about grit–tenacity, working through a process, and not giving up when failure seems imminent. Statistically, over half of people say they ‘succeeded’ (in whatever venture they tried) not by being the best in the field but because they were the last man standing.

Integrate that into your lessons. Assess student effort, their attention to detail, their ability to transfer knowledge from earlier lessons to this one, their enthusiasm for learning, how often they tried-failed-retried, and that they completed the project. Let students know they will be evaluated on those criteria more than the perfection of their work.

Let students teach each other

There are many paths to success. Often, what works for one person is based on their perspective, personal history, and goals. This is at the core of differentiation: that we communicate in multiple ways–visually, orally, tactally–in an effort to reach all learning styles.

Even so, students may not understand. Our failure to speak in a language they understand will become their failure to learn the material. Don’t let that happen. Let students be the teachers. They often pick a relationship or comparison you wouldn’t think of. Let students know that in your classroom, brainstorming and freedom of speech are problem solving strategies.

Don’t be afraid to move the goalposts

Even if it’s in the middle of a lesson. That happens all the time in life and no one apologizes, feels guilty, or accommodates your anger. When you teach a lesson, you constantly reassess based on student progress. Do the same with assessment.

But make it fair. Let students know the changes are rooted in your desire that they succeed. If you can’t make that argument, you probably shouldn’t make the change.

Success is as much serendipity as planning

Think of Velcro and post-it notes–life-changing products resulting from errors. They surprised their creators and excited the world. Keep those possibilities available to students.

Don’t reward speed

Often, students who finish first are assigned the task of helping neighbors or playing time-filler games. Finishing early should not be rewarded. Or punished. Sometimes it means the student thoroughly understood the material. Sometimes it means they glossed over it. Students are too often taught finishing early is a badge of honor, a mark of their expertise. Remove that judgment and let it be what it is.