Category: International

Multimedia content personalizes learning

Ask a Tech Teacher contributor, Josemaría Carazo Abolafia, is an educational researcher and teacher who lives in Spain–and doesn’t own a car! He has a Masters in Ed from Penn State University (any Nittany Lion fans out there?) and is working on his EdD. Josemaria and I share the belief that “…[technology] must be transparent, like a lens; otherwise, it hinders learning.” Here’s his take on the use of videos in education:

Multimedia content as a way to learning process personalization

People can learn more deeply from words and pictures than from words alone. It can be called the multimedia learning hypothesis (Mayer, 2005). My experience teaching with videos supports the idea that students not only learn more deeply but also faster. Consequently, the syllabus can be enlarged when classes take advantage of multimedia means -as it happened.

Moreover, multimedia content helps to individualize the learning process for every student, who really can learn at its own pace.

The multimedia content that I use consists of about 250 videos. Most of them are between 2 and 5 minutes long. Each video contains an explanation that happened during a real class, recording what students were watching -classrooms have a projector- and listening. They can be checked out at http://youtube.com/ldts1. It might be important to point out that my students are 17 years old and over.

However, using multimedia content to elicit learning does not lack inconveniences. The same problems that hinder learning when using textbooks occur when using videos. On the other hand, the same techniques can be useful in both cases. A constructivism insight and the cognitive load theory ground the solutions proposed to avoid those inconveniences.

Three difficulties when using multimedia content

I mainly found 3 difficulties when using videos as the main learning content format:

-

- Reception overload. More frequently than wished, the student doesn’t get the gist of an explanation on video format, and she or he has to re-watch the video 1, 2 or even 3 times. There’s no doubt, it’s frustrating for anyone.

- Lack of learner’s intervention. Passivity.

- Lack of variety -not related to the content but the format: video, text, website, lecture, and so on.

Based on several learning theories, I focused on 3 ways to tackle these problems.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

How to Grow Global Digital Citizens

With the rise of online games, web-based education, and smartphones that access everything from house lights to security systems, it’s not surprising to read these statistics:

With the rise of online games, web-based education, and smartphones that access everything from house lights to security systems, it’s not surprising to read these statistics:

In 2013, 71 percent of the U.S. population age 3 and over used the Internet

- 94% of youth ages 12-17 who have Internet access say they use the Internet for school research and 78% say they believe the Internet helps them with schoolwork.

- 41% of online teens say they use email and instant messaging to contact teachers or classmates about schoolwork.

- 87% of parents of online teens believe that the Internet helps students with their schoolwork and 93% believe the Internet helps students learn new things.

Since so many kids come to school with a working knowledge of the Internet, teachers feel comfortable using it as a teaching tool but just because students use the Internet doesn’t mean they do it safely and wisely. In fact, despite that the UN considers access to the Internet a human right, many adults and even more kids don’t know how to act as good digital citizens when visiting this sparkly and exciting world. When they first arrive, all of life’s rules seem to be upended. Users can be anyone they want, break any cultural norm and even be anonymous if they’re careful, hiding behind the billions of people crowding around them.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

22 Tips on How to Work Remotely

I first considered this topic at a presentation I attended through WordCamp Orange County 2014. I had several trips coming up and decided to see how I addressed issues of being away from my writing hub. Usually, that’s when I realize I can’t do/find something and say, “If only…”

I first considered this topic at a presentation I attended through WordCamp Orange County 2014. I had several trips coming up and decided to see how I addressed issues of being away from my writing hub. Usually, that’s when I realize I can’t do/find something and say, “If only…”

I am finally back from three conferences and a busy visit from my son–all of which challenged me to take care of business on the road and on the fly.

Truth is, life often interferes with work. Vacations, conferences, PD–all these take us away from our primary functions and the environment where we are most comfortable delivering our best work. I first thought about this when I read an article by a technical subject teacher(math, I think) pulled away from his class for a conference. Often in science/math/IT/foreign languages, subs aren’t as capable (not their fault; I’d capitulate if you stuck me in a Latin language class). He set up a video with links for classwork and a realtime feed where he could be available and check in on the class. As a result, students–and the sub–barely missed him. Another example of teaching remotely dealt with schools this past winter struggling with the unusually high number of snow days. So many, in fact, that they were either going to have to extend the school year or lose funding. Their solution: Have teachers deliver content from their homes to student homes via a set-up like Google Hangouts (but one that takes more than 10-15 participants at a time).

All it took to get these systems in place was a problem that required a solution and flexible risk-taking stakeholders who came up with answers.

Why can’t I work from the road? In fact, I watched a fascinating presentation from Wandering Jon at the Word Camp Orange County 2014 where he shared how he does exactly that. John designs websites and solves IT problems from wherever he happens to be that day–a beach in Thailand, the mountains in Tibet or his own backyard. Where he is no longer impacts the way he delivers on workplace promises.

Here’s what I came up with that I either currently use or am going to arrange:

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

Chinese Class vs. American Class

An efriend and former NYC teacher, Steve Koss taught in China (winner of a top spot on the annual PISA best-education-in-the-world) for part of his career and was not surprised China came out with some of the best test scores in the world. He shared his experience while teaching there. Compare what he saw to what we have here in America keeping in mind that we languish somewhere below middle on that international PISA test.

An efriend and former NYC teacher, Steve Koss taught in China (winner of a top spot on the annual PISA best-education-in-the-world) for part of his career and was not surprised China came out with some of the best test scores in the world. He shared his experience while teaching there. Compare what he saw to what we have here in America keeping in mind that we languish somewhere below middle on that international PISA test.

- Every classroom was a bare, cinder-block-walled enclosure, no heat in the winter, no cooling in the early summer, virtually nothing decorating the walls. Students spent their entire school day in the same room – teachers came to them.

- Every classroom held 48 – 50 students, lined up in traditional, ramrod-straight rows. Textbooks and workbooks for students’ full set of the day’s classes were piled on and under their desks – no one had a locker.

- Teachers lectured from a dais at the front of the room. Students sat quietly at their desks and listened, took notes, occasionally recited in unison or responded, standing, to a direct question from the teacher. Questions from students were a rarity.

- Many, if not most, lectures were straight from students’ texts, sometimes nothing more than

- teachers simply reading from the textbook.

- Teachers appeared at students’ classrooms just before lessons began, departing back to their subject area offices immediately upon finishing their lessons. Casual student-teacher interaction was minimal at best. Teachers spent much of their office time (they only taught two class periods per day) playing video games and reading the daily newspaper.

- Copying of assignments was rampant – and tolerated. As, all too often, was cheating on exams. Scores counted more than how they were achieved.

- I saw no evidence of what in the U.S. we would call “student projects.” Classroom activity appeared to be the same lecture and recitation style every day.

- Students were actively discouraged from asking questions. I was told on more than one occasion that students’ parents could actually be called into the school so that a teacher could complain that the child was disrupting lessons because he/she was asking too many questions.

- Schools had no clubs or activities and minimal if any organized sports teams. One school where I worked claimed to have two or three interscholastic sports teams, but only for boys.

- Students typically took seven or eight classes each semester, leaving no time for activities even outside of school.

- Never once among the hundreds of students I saw and taught did I see a student with a physical handicap or a visible learning disability. I don’t know where those students were, or if they were even still permitted to attend school by high school age, but if so, there was no inclusion.

- Physical education consisted mostly of lining students up in straight rows and performing low-impact calisthenics and movement.

- The last semester of senior year is dedicated nearly exclusively to preparation for the gaokou, the national, three-day-long, college entrance examination.

- Schools were evaluated, and principals and teachers rewarded, according to their students’ standardized exam results.

- Teachers earn extra income from tutoring. They are allowed to accept money from their own students (or gifts from those students’ parents), a sure-fire disincentive to effective teaching in the classroom setting.

- There was no parent involvement in the schools whatsoever. Parents visited a school for only one of two reasons: to be roundly chastised for their child’s behavior/performance, or to present a gift for extra tutoring services rendered.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

Educational Advice From Finland

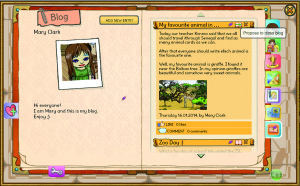

I’m thrilled to have Maria Lindqvist from Finnish educational social media platform, Petra’s Planet for Schools, as my guest here today. She shares her advice on using social media safely and effectively in schools.

21st century learning using social media

Advice from Finland

Social media doesn’t have a place in the learning environment; it is simply a tool for people to keep their friends up to date with their lives…or is it?

If we look at the process of social media we can start to consider its place in the learning environment. Taking Facebook as an example of a social media site, as use rs we set up a personal page and profile and start to communicate with our friends. We want the information we write to be interesting, amusing and informative; how do we best convey the message we want to get across? We read messages from other friends and if their communication is worthy we chose to ’like’ it. Writing effectively can therefore decide how many ‘‘likes’ you receive; an important thing for young people. We then have to decide whether we want to illustrate the message with an associated picture image; this can’t be too large a file size so we may need to use a graphics editor to resize the image.

rs we set up a personal page and profile and start to communicate with our friends. We want the information we write to be interesting, amusing and informative; how do we best convey the message we want to get across? We read messages from other friends and if their communication is worthy we chose to ’like’ it. Writing effectively can therefore decide how many ‘‘likes’ you receive; an important thing for young people. We then have to decide whether we want to illustrate the message with an associated picture image; this can’t be too large a file size so we may need to use a graphics editor to resize the image.

One of our Facebook friends could be someone from Turkey who we met on holiday last year. She writes about her family’s religion and the celebrations she attends. Her prayer in the mosques is called namaz, but generally she prays at home. Over the summer she is going to work at a farm in her village, picking fruit which is the most common type of work in her remote area of Turkey. Suddenly I have a new interest in this country and want to understand its cultures and economy. When we start to study world religion in school, I contact my friend to gather information. It is so much more real coming from her than from a book.

It is clear to see the potential educational benefits of social media in the classroom.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

5 Reasons Class Size Does NOT Matter and 3 Why Large is a Good Thing

Are you drowning in students, sure that the flood of bodies that enter your classroom daily will destroy your effectiveness? Does it depress you, make you second-guess your decision to effect change in the world as a teacher? Do you wonder how you’ll explain to parents–and get them to believe you–that you truly CAN teach thirty students and meet their needs (because you must convince them–of all education characteristics, parents equate class size to success)?

Are you drowning in students, sure that the flood of bodies that enter your classroom daily will destroy your effectiveness? Does it depress you, make you second-guess your decision to effect change in the world as a teacher? Do you wonder how you’ll explain to parents–and get them to believe you–that you truly CAN teach thirty students and meet their needs (because you must convince them–of all education characteristics, parents equate class size to success)?

Take heart while I play Devil’s Advocate and offer evidence contrary to what seems by most to be intuitive common sense. I mean, how could splitting your finite amount of time among LESS students be anything but advantageous? Sure, there are many studies (US-based primarily) that support a direct correlation between class size and teacher ability to meet education goals, but consider how you–personally–learn. Sure, it occurs through teachers, but just as often by trial and error, peers, inquiry, student-centered activities, play, experiencing events, differentiated ways unlike others. Educators like John Holt believe “children [and by extension, you] learn most effectively by their own motivation and on their own terms”.

Is it possible the root of the education problem is other than class size? Getting Beneath the Veil of Effective Schools: Evidence from New York City (National Bureau of Economic Research) indicates that traditional success measures–including class size–do not correlate to school effectiveness. According to this study, what doesn’t matter is:

- class size

- per pupil expenditure

- fraction of teachers with no certification

- fraction of teachers with an advanced degree

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More