Dr. Bill Morgan is a frequent contributer to Ask a Tech Teacher. Today, he is sharing his experience and research on how keyboarding skills benefit other topics I found this every interesting:

Finger Dexterity

Transferable Keyboarding Skills

Dr. Bill Morgan, Ph.D.

“How do you play the piano as well as you do?” someone in the choir asked me last Sunday. The choir director had apologized as he handed me an arrangement that I had never seen before, saying, “I should have given this to you earlier.” I reassured him, “If you pick ‘em I’ll play ‘em.” I have learned to play not only all of the hymns in the book but most choir arrangements, as well.

I have since reflected on how I had accompanied school choirs and solo ensemble students from both the band and the choir while I was still attending high school. As I was playing a Beethoven sonata my piano teacher praised the amount of practice that I had put in that week, but the truth was I had only warmed up for an hour before the lesson. While attending a junior college I was paid to accompany a choir while taking the class for credit.

What was it that enabled me to sight read piano music? Something more than the fact that my mother started teaching me, in our home, at age six. While teaching piano students as young as four and as advanced in years as 84, I teach more than just the names of the notes. I encourage my students to practice more than the scales with correct fingering.

Have you ever read or heard the claim that musical instrument students excel in academics? The skill of reading musical symbols from left to right and from top to bottom on each page at an early age helps students learn to read pages in books from left to right. Math skills are also used as we turn the pages in a book.

But, it has to be more than counting numbers and the discipline that comes from daily practice. We don’t just teach and model the correct fingering. We don’t just demonstrate the time signature and number of beats per measure. Our students also learn the distance between the notes, which musicians call “intervals.” Intervals are defined by piano teachers as the number of keys skipped from one key to the next, plus two. For example, as we stretch our fingers to play an octave, from “middle C” up or down to the next C, we count both C keys and the six in between. “Just like an octopus has eight legs,” I tell my young pianists, “an octave has eight keys.”

This morning, before school, I was teaching three brothers in the same family. The youngest child was learning the name of each key, A through G, but the middle child was learning intervals. “When I put my right thumb on C and then use my second finger on D, what interval is that?” He correctly answered “a second.” I praised him and then asked, “when I put my right thumb on C and my third finger on E, what interval is that?” We repeated the question and answer series for fourth and fifth fingers, then extended to sixth and seventh intervals.

That might have been how I developed sight reading skills while accompanying soloists and choirs. I was subliminally applying math skills to guide my fingers across intervals of keys on the piano keyboard. I knew the location of the starting note, whether in the Treble or the Bass Clef. I also recognized the intervals in the music, as I explained to my student this morning: “Moving from line to space or space to line has to be an even number; second, fourth, sixth, or eighth.” I then pointed out that line to line or space to space is an odd number: “third, fifth, or seventh.” Eureka! I was teaching math along with music.

When we first teach phonics to early readers, we tell them to “sound it out.” We then teach “sight words” that break the rules of phonics. When “good readers” read aloud they read ahead of the words to be pronounced, so as to add voice inflection and correct pronunciation to the read aloud presentation.

As I trained my daughter to turn pages for me, at the piano, I asked her to turn a full measure before I reached the bottom of the page. I was actually reading ahead one measure and momentarily memorizing the upcoming notes. I had to see the first measure on the next page before the soloist or choir got there.

We might also do that for our computer literacy students learning to take dictation. Words that sound the same might change spelling in context; for example, “to, too, or too” and “their, there or they’re.” When editing we can also run-on sentences by adding punctuation.

The Transfer of Skills

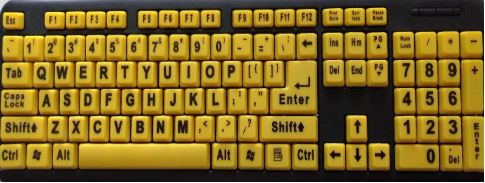

How, then, does finger dexterity transfer from piano keyboarding to computer literacy? When teaching computer keyboarding skills to novice computer students, we begin by asking them to line their fingertips up on the “Home Row,” which includes “A S D F” for the left hand fingers and “J K L semicolon” for the left hand. We train our fingers one at a time on each key: “AAA SSS DDD FFF” and so on, then practice reaching up and curling down to the keys on the top and bottom rows of the keyboard.

We train our fingers using repetition to develop muscle memory and automaticity. Dexterity is a word we use to describe eye hand coordination. Over time we learn to combine keystrokes as we spell words and form them into sentences, adding punctuation. The letters appear as we type them, in the same direction that we read English, from left to right and from top to bottom on the monitor.

“Keep your eyes on the copy,” we were told in our business typing classes in the 1970s. Do we still do that, or do we encourage our students to compose freestyle, “at the speed of thought,” while looking at the words on the computer monitor. If, as we so often do when texting on a cell phone, we look down at the keyboard and then up at the monitor, it slows us down. The same occurs when piano players look down at the keyboard and back up to the sheet music.

Louis Hanon became famous for designing piano exercises that train fingers using intervals. Someone out there might be teaching intervals, like the distance between letters, on computer keyboards. I did that, once in a college programming class. I wrote the code to move a LOGO turtle from A to B and from B to C on a QWERTY style keyboard layout. There are two sets of three letters in alphabetical order on the “home row” of letters. Do you see them? F G H and J K L. Do you also see sets of two letters in alphabetical order? Letter keys N and M are in order from left to right, near the space bar. Letter keys O and P are in order from right to left. Then there is that separation of P and Q, perhaps because the type setters who designed the QWERTY keyboard had to pay close attention to the lower case p’s and q’s, which could be easily reversed.

My LOGO turtle navigated those letters with ease. The turtle also stamped the odd numbers along the row of number keys above the top row of letters: 1 3 5 7 9 with two steps between stamps similar to intervals. It then turned around and stamped 8 6 4 2 with similar intervals. This reminded me of a hopscotch game we played on our elementary playground in the 1960s.

Author bio:

More on Keyboarding

5 (free) Keyboarding Posters to Mainstream Tech Ed

A Conversation about Keyboarding, Methods, Pedagogy, and More

Tech Ed Resources–K-8 Keyboard Curriculum

Jacqui Murray has been teaching K-18 technology for 30 years. She is the editor/author of over a hundred tech ed resources including a K-12 technology curriculum, K-8 keyboard curriculum, K-8 Digital Citizenship curriculum. She is an adjunct professor in tech ed, Master Teacher, webmaster for four blogs, an Amazon Vine Voice, CSTA presentation reviewer, freelance journalist on tech ed topics, contributor to NEA Today, and author of the tech thrillers, To Hunt a Sub and Twenty-four Days. You can find her resources at Structured Learning.