To students, knowing how to ‘compare and contrast’ sounds academic, not real world, but we teachers know most of life is choosing between options. The better adults are at this, the more they thrive.

Common Core Standards recognize the importance of this skill by addressing it in over 29 Standards, at every grade level from Kindergarten through Twelfth Grade. Here’s a partial list:

Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take. (K-5 and 6-12 Reading Anchor Standards)

Compare formal and informal uses of English (2nd grade Language Standards)

It also appears multiple times for most grade levels in the Math Standards, including the Standards for Mathematical Practice. Why is this skill so important? Look at what Harvey Silver says in his book, Compare and Contrast:

By compiling the available research on effective instruction, Marzano, Pickering, and Pollock found that strategies that engage students in comparative thinking had the greatest effect on student achievement, leading to an average percentile gain of 45 points. More recently, Marzano’s research in The Art and Science of Teaching (2007) reconfirmed that asking students to identify similarities and differences through comparative analysis leads to eye-opening gains in student achievement.

Clearly, this is a seminal skill.

Whenever I have a chance, I ask students to make a choice between two–or more–digital tools that can be used to solve a problem or prepare a project. I don’t want to make the decision for them; I want them to mentally compare and contrast. I want them to hone their abilities to reach an ‘if-then’ conclusion. I hope they can convince me they have a better approach than I do. For example, if I ask them to write a report using a word processing tool (Word, Google Docs), they are welcome to convince me a slideshow or video would be a better choice, but they have to make their argument based on logic and evidence, comparing and contrasting their approach to mine.

Offering options in the digital tools they use to communicate their knowledge encourages students to take responsibility for their own learning and you as the teacher to differentiate for their needs without a lot of extra work.

It starts with a change in mindset: You aren’t teaching a tech tool, you’re teaching its application to learning.

For example, using the book report scenario, discuss these with students:

- What are the basics of each reporting method?

- Slideshows benefit oral presentations

- Word processing reports are typically submitted, not presented

- Spreadsheets are used to simplify numbers, often part of a bigger reporting method

- Desktop publishing provides a take-away that can be consumed in chunks

- Compare/contrast these differences and how the student wants to communicate. That will help him/her reach a decision on their best choice

The first time you present this sort of decision matrix to students, they may ask you to pick for them. Resist. Help them evaluate their personal strengths and weaknesses, but the ultimate choice is theirs. You might provide them with a spreadsheet such as this (3rd grade and up–after they’ve been introduced to the use of slideshows, word processing, spreadsheets, and desktop publishing):

But–leave half the cells empty. Ask them to work in groups to complete the table. Think about the categories and how each tool applies. Here’s what that might look like:

Adapt the table to the tools they have available. For example, you might want to add videos, decision matrices, and audio podcasts.

Once they’ve gone through this once with you, they can reproduce it every time they are faced with the question of what digital tool best fits a project.

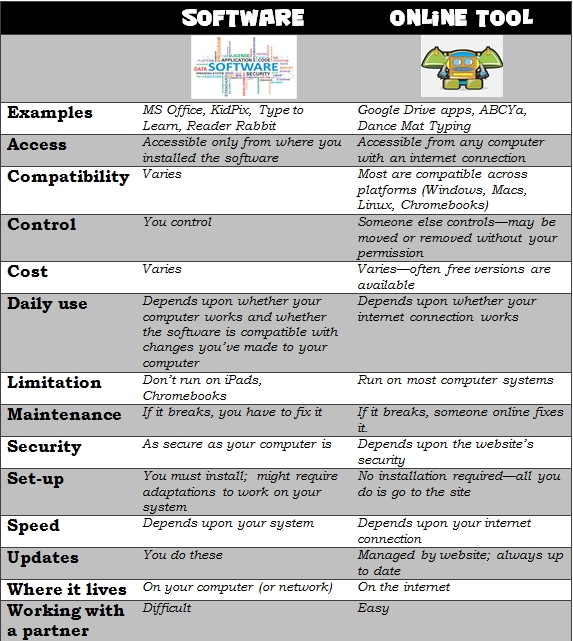

Besides using compare-contrast to select digital tools, it is also useful in teaching concepts that are otherwise confusing, like the difference between software and online tools. Build a table with students that includes all the pertinent parts and then fill it in together. I start this in 1st grade, when students have used both software and online tools and likely don’t realize they’re completely different tools. The table helps them to compare and contrast relevant characteristics. Here’s an exemplar of what that table might look like:

Too often, students want the teacher to make decisions for them. They forget–or don’t realize that the critical thinking and problem solving skills they learn in school and life can be applied everywhere. Compare-contrast is an organic skill that will become part of their life skills toolkit, once they understand how to use it.

Jacqui Murray has been teaching K-18 technology for 30 years. She is the editor/author of over a hundred tech ed resources including a K-12 technology curriculum, K-8 keyboard curriculum, K-8 Digital Citizenship curriculum. She is an adjunct professor in tech ed, Master Teacher, webmaster for four blogs, an Amazon Vine Voice, CSTA presentation reviewer, freelance journalist on tech ed topics, and author of the tech thrillers, To Hunt a Sub and Twenty-four Days. You can find her resources at Structured Learning.